An Insider into Sabae: the Lacquerware Town

Nestled along Japan’s Western coast, Sabae is a jewel on the Takumi Road, a historic trail in the Hokuriku region that celebrates Japan's most esteemed craftsmen. Here lies a sanctuary of winding roads, blue-tiled roofs, and rice fields soaked in summer, where generations of artisans have silently honed the art of Echizen lacquerware. When Kyomi ventured here to listen to the craftsmen, we found ourselves enveloped in the world of Echizen lacquerware, welcomed with much warmth into a town rich with cultural heritage.

The Lacquerware Craftsman Houses

“Is it this one?”

We peered out of the car window, searching for the craftsmen’s site. In a network of narrow roads and sliding doors, it could be any one of the unassuming houses.

“That one,” Our cameraman pointed to a door with a box of azaleas, an elderly lady waiting by its side. “That’s it.”

As we stepped into the wooden interior, the air was thick with the distinct smell of Urushi lacquer. There was a steady hum of tools, of wood whirring against sandpaper in steady, rhythmic motions. As artisans at the first stages of lacquerware production, master craftsmen and young apprentices worked side by side, polishing bowls and doing quality checks at various work desks. Bowls and spoons were stacked in various shades and stages of completion, and a methodical purposefulness filled the room.

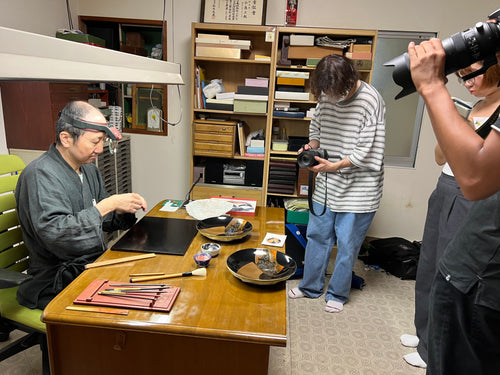

The lacquerware production occurs in stages, so there is a separate house for the final Maki-e painting. In this process of nearly microscopic detail, no machinery is involved but his magnifying glasses. Much about this space feels different from the previous studio — unlike the communal workspace of the lacquer painters, this small tatami-floored room is secluded from the rest of the building, the temperature lower, a stoic silence hinting at the level of precision Maki-e painting demands. Apart from a central work station, the room is filled with cabinets of fine brushes and powders of precious metals. I wonder what the artisan thinks of as he paints each hair of a hare’s back, quietly accompanied by the golden phoenixes and trees he has previously breathed life into.

Katayama Shikki, The Shrine of Koretaka Shinno

A short journey from the lacquerware houses brought us to a sacred site: the Shinto shrine of Koretaka Shinno, dedicated to the god of lacquerware and the first son of the 55th Emperor Montoku. Nestled in the embrace of lush mountains, it stands as a monument to the divine patron of lacquerware. According to the shrine caretakers, in the 9th century, Prince Koretaka Shinno played a pivotal role in the birth of the manufacturing industry by teaching locals how to process wood with a potter's wheel. This led to the birth of the "Kijishi" (woodturners), who revered the prince as the ancestor of their craft. Combined with the local lacquer-scraping tradition, this knowledge laid the groundwork for what would become a renowned center of lacquerware production.

In gratitude to the prince, the craftsmen of Katayama built the shrine in 1221 and enclosed within it a precious historical book in Omi Province, then a popular hub for woodworkers. After being destroyed by the Isewan Typhoon in 1959, the shrine was rebuilt in October 1964. Today, it stands as a serene testament to the enduring respect the artisans hold for their craft's origins, surrounded by the forest of a nearby mountain. The shrine doors are usually shut, but they open once during Sabae’s annual festival. Hidden within the small structure is a small table, two rows of rectangular gold panels hung vertically upright — according to the two shrine caretakers, they symbolize the boundary between the earthly and divine realms. Standing beneath the stone Torii gates, we took a moment to contemplate what we had just learnt.

Our photographer rang the shrine’s bell before we left. It made a clear, echoing sound.

The Lacquerware Museum

In the outskirts of the town, the lacquerware museum stands as a custodian of the town's rich artisanal history. This modest building, with its display cases and historical records, chronicled the evolution of lacquerware with meticulous care, showcasing the craftsmen’s journey from ancient tools to contemporary innovations. Encased with a glass display, the tools used in the early days of lacquerware production were preserved and presented with pride.

There is a local legend about the origin of Echizen lacquerware, situated long before Prince Koretaka Shinno came about. In the 6th century at the end of the Kofun period, a painter from the Katayama village was commissioned by the 26th Emperor Keitai to repair a broken crown using lacquer. The painter returned bearing not only a perfectly melded crown, but also the gift of a simple lacquer bowl. His skill impressed the prince so significantly that the latter encouraged the production of lacquerware in Katayama village, sowing the seeds for what would become a blossoming international trade. Today, some companies such as Yamada Heiando still retain ties to the Imperial family.

Our guide and supervisor of the artisans, Mr Tominaga, shared stories of lacquerware's evolution, pointing out the subtle changes in design and technique that marked different eras. At the entrance, Mr. Tominaga showed us the personal collection of historical documents he keeps at home. Detailing transactions and trade from the early 20th century, the records offered a remarkable glimpse into the lives of the artisans and the significance of their work in the broader context of history.

The Lacquer Posts

As we continued our exploration, the red lacquer posts that dotted the landscape caught our attention. These signposts, a vibrant red against the backdrop of green fields, serve as markers of Sabae's identity as a heritage town, describing its association with Echizen lacquerware and its long history with art. Each post, with its distinctive hue, was just a shade brighter than the paint used for tableware of Echizen lacquerware.

Driving past these posts, I was touched by how deeply the town’s artistic history permeates through the geography of people’s lives. Far from being relegated to history, they stood as emblems of a culture that had been woven into the very fabric of the town, sincere in their unassuming yet striking way. The presence of lacquerware in Sabae is ubiquitous, a reminder of the communal dedication necessary to preserve its cultural heritage. Stationed along the fields like beacons, these posts felt like a living, breathing part of their community.

The Springwater Drinking Site

Our journey in Sabae culminated in a serene moment by a spring, hidden beside a burbling stream and shadowed by a mountain draped in sun-dappled trees. Accompanied by the rustling of a sun-dappled forest, it was a pleasant serenade to our experience, offering a brief respite from the summer heat and the freshest water I’ve ever drank.

In Sabae, we found more than just a town; we discovered a community where their hospitality is as sincere as their respect for their artisanal roots. This town, with its unassuming warmth and deep-seated pride in its craft, is a living testament to the enduring spirit of the Takumi. As we departed, the memory of Sabae's springwater lingered, a refreshing reminder of the artistry we had been privileged to witness.

Ready to explore our wide range of products? Visit our catalog pagenow and discover the perfect items for your needs!